As a kid, drills were the ultimate tool. They made noise. They were easy to use. And they had the ability to destroy stuff. Now, drills are everywhere – in DIY toolkits, construction sites, workshops, dentists, operating rooms. And I’ve got several. Like I’m sure you do too.

But when I was using mine the other day, it got me thinking… “What's the drill with drills? Like where did they come from? And how did we get to this handheld buzzbot in my hand right now?”

For a tool that achieves something so refreshingly simple (a hole), I was curious to learn more. So, allow me to coherently explain my findings from this undrillable rabbit hole and share them with you.

The awl-some starting point

Early humans discovered that rotating a stick against a surface could bore a hole. Groundbreaking. Literally. And it has shaped human progress for a long, long time.

The very first drilling tools were primitive awls (sharp stones fixed to sticks rotated by hand to puncture things like bone, ivory and wood). Archaeological finds date these to ~35,000 years ago, showing just how fundamental drilling was to our ancestors.

Soon after came the “strap drill”, where a leather strap wrapped around a shaft was pulled back and forth, spinning the tip faster. These usually had a socket or pad at the top to stabilise it, but keep it moving freely.

This principle was then refined into the bow drill – one of humanity’s first “machine drills”. It was popularised ~6000 years ago in Egypt, and converted back-and-forth motion (of a bow) into a rotary motion.

You tied a cord around a stick, which held the bit, and attached the ends of the cord to the ends of the bow.

This was a particularly useful development because it made starting fires much easier, and obviously continued our hole-some chain of drill development.

Open wide. Really wide.

One of the coolest findings related to this is from Mehrgarh, Pakistan.

Evidence shows that flint-tipped drills were used in early dentistry, boring into human teeth with somewhat respectable precision. Although I can’t confirm how painful or awkward this was…

Well, well, well…

In China (circa 500 BCE), inventors developed the churn drill. Using suspended weights and ropes to pound rock, these percussion drills could reach staggering depths of 1500m!

They were used for well-drilling centuries before Europe adopted similar methods (sometime in the 12th century).

Drilling at its core

As civilisations advanced, so did drilling. Egyptians invented the ‘core drill’ using rotating copper tubes with abrasive slurry to cut cylindrical (removable) plugs from stone. This is often seen as a direct ancestor of today’s hole saw.

Around the same time, the pump drill offered a new twist on the bow drill. Rather than a bowstring, it used a crosspiece that slid up and down the spindle. Each downward push spun the bit, while a flywheel kept the motion going and rewound the cords for the next stroke. The result was faster, smoother drilling with greater pressure.

Roman Aug(er)mentation

By the Iron Age and into Roman times, the auger came into play.

Early versions had a simple crossbar handle and a sharpened end, resembling a split pipe. Users had to stop every now and then to clear the shavings. But the Romans did what Romans did and developed it. They refined it into a corkscrew-shaped bit fixed to a T-handle. Its helical blade cut as it turned and carried waste out of the hole. Perfect for deeper, cleaner bores.

Smaller versions, known as gimlets, offered fine control for delicate tasks – and these boring little helpers are still used by woodworkers today.

Brace yourself

During the Medieval period, drills became more ergonomic and efficient. The brace and bit, first depicted around 1425, had a U-shaped crank with a rotating spindle. For the first time, users could apply continuous torque without exhausting themselves.

Although that still seems pretty exhausting compared to now…

Then came interchangeable bits/braces. And metal reinforcements. Even ratcheting mechanisms to let them operate in small spaces. Drilling was about to boom.

Torque meets technique

The Renaissance’s emphasis on mechanics gave drills new refinements. Augers grew more sophisticated, while craftsmen experimented with breastplates to apply more torque.

And by the 19th Century, advances in steelmaking and machining transformed drills…

Geared handles used a side crank and gears to spin the bit faster than the handle turned. Breast drills allowed users to lean into the tool with chest pressure, ideal for harder, tougher materials. Push drills and spiral screwdrivers introduced spring-loaded mechanisms for small, precise work.

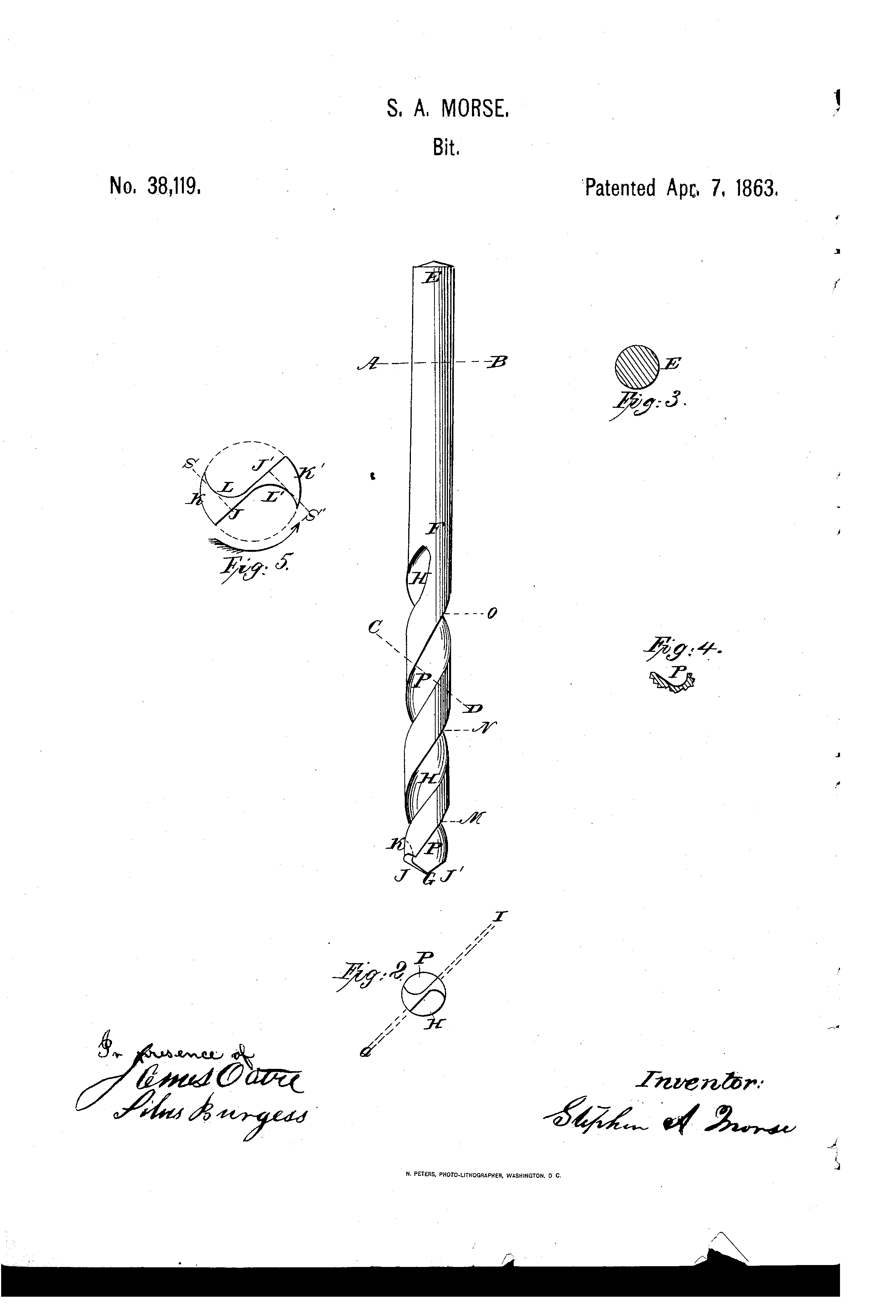

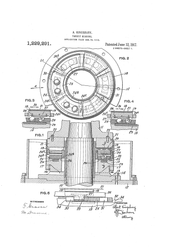

But arguably, one of the most important developments came in 1861.

Source: Google Patents

Wired for innovation

The Industrial Revolution brought power to progress and electricity to drills.

In 1889, Aussies Arthur Arnot and Willian Brain patented the first electric drill. This was heavy and stationary, more geared towards mining than workshops.

In 1891, the Goodell Brothers patented a push drill with bit storage inside the handle. A small but clever improvement. Maybe an early ancestor of the MetMo Pocket Driver…

Stephen A. Morse of Massachusetts invented the twist drill bit, patenting it in 1863. Its spiral flutes efficiently cleared chips and prevented jamming – a design so effective it remains the global standard today.

Then, in 1895, German brothers Wilhelm and Carl Fein created the first portable electric drill – though it still required two hands.

But the real breakthrough came in 1917, when S. Duncan Black and Alonzo G. Decker, founders of Black & Decker, became the torque of the town with a pistol-grip, trigger-switch drill.

This was inspired by the Colt revolver which happened to be lying around in their shop at the time. The ergonomic one-handed design became the blueprint for nearly every drill since. And by the 20s, drills were entering homes just as much as factories. Black & Decker even deployed mobile training buses to teach retailers how to sell this new category of power tool.

In 1924, A.H. Petersen created a lightweight drill nicknamed the “Hole Shooter”. After his workshop burned down, Milwaukee Tool took over the design and turned it into a professional standard.

Cutting the cord

The next revolution was the freedom from cords. In 1961, Black & Decker introduced the first cordless drill, powered by nickel-cadmium batteries. They were initially intended for industry, but soon reached consumers and DIY-ers.

A Japanese firm, Makita, squeezed the trigger on the cordless market. And in 1978, they released the 6010D – the first removable battery drill available to the public.

But cordless drills also had a cosmic chapter.

In the 60s, Black & Decker collaborated with NASA to design battery-powered drills for the Apollo missions. These “moon drills” could operate in zero-gravity, extreme cold, and a vacuum, extracting rock samples on the lunar surface.

And of course, everyone wanted one. (I still do)

Drills go digital

By the late 20th century, nickel-cadmium batteries gave way to lithium-ion cells, which were lighter, more powerful, and faster to recharge. And other innovations followed.

There were brushless motors that increased efficiency and tool life. Digital torque controls gave users precision across materials. Laser guides and electronic levels improved accuracy. And even more recent bluetooth tracking and smart sensors linked drills into tool ecosystems to track location, adjust settings and track usage in jobsite dashboards.

Today, drills range from compact 12V screwdrivers to 60V rotary hammers that pulverise concrete. And specialised forms (like impact drivers, drill presses, magnetic drills, and hammer drills) show how far the family of drills has diversified.

Keep the past in rotation

Despite their decline after electrification, manual drills remain beloved and held close to the hearts of many. Myself included. And craftsfolk and enthusiasts still reach for them for several reasons.

They’re precise. Hand control avoids over-drilling and splitting wood. Or at least give you a bit more time to realise you’ve gone too far…

They’re quiet. No motors droning on. Just the sweet sound of gears and drilled wood.

They’re a token of the past. And they gift the immeasurable feeling of something handheld. A huge part of what we do (and why) at MetMo.

So, manual drills might not be the most efficient. But they are certainly the most satisfying.

A hole lot of history

So, from prehistoric fire-starting and make-shift dental treatments to smart drills and laser guides, the history of manual drills is quite the story of human ingenuity. And it’s one that goes round and round, up and down… (I had to get at least one cheesy joke in there…)

Each innovation has built on the last, progressively refining the wonderful art of making a hole.

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading this. If you did, let us know in our CubeClub forum or MetMo subreddit. We have another historical deep dive here: on collets.

If you’re the kind of person who also enjoys putting handheld holes in wood, I have a couple of tools you might like.

MetMo Driver

Our larger high-torque driver that’s more powerful than most battery screwdrivers…

It’s here: The MetMo Driver

MetMo Pocket Driver

Like the above, but even smaller. The perfect companion for flatpacked furniture or huge wooden holes.

It’s here: The MetMo Pocket Driver

Share:

Take A Look At Our Little Bits

How to Grow Your Fractal