There are no two ways about it. I have too many tools. I’ve got workshop tools, model-making tools, woodworking tools, even tools for my tools. I’m addicted to them. Proudly.

So I think it’s fair to say that I spend too much time looking at them. Some are waaay cooler than others, some more functional than others. And well, MetMo being such a big part of my life, you probably understand that I’m also a little obsessed with tool design.

So today, you’re going to join me on a path of ‘obsession exploration’ as I explain what I think are some of the best-designed tools.

Some principles behind good tool design

What feeds into the best tool design? A lot of things. And one of the many wonders of creative endeavours is that there are countless contradictions. So sometimes even the most ‘tried and tested’ rules are meant to be ripped to shreds.

One aspect that comes to mind is ‘invisibility’. I know that sounds all deep and philosophical (and cliché), but I think great tools should remove friction. Friction you didn’t realise you were spending energy on. They should almost disappear into the abyss, leaving just you and the all-essential tinkering that requires your undivided attention on a Sunday afternoon.

Frictionless…

If I generalise, then I think the best hand and EDC tools all obey a similar set of principles, or underlying rules. Before we look at the tools, let's look at the rules. Here are five of the most important.

User-first

Great tools are designed around real people doing real jobs. That means considering grip strength, hand size, left- or right-handed use, fatigue, gloves, low light, and the environment in which the tools actually live. They’re almost like my aunt after a few wines: opinionated. They know who they’re for and who they’re not.

Reduce friction (not the literal sort)

Another cliché for you: the best tools should require no explanation. You instinctively know how to hold, orient, and use them correctly within seconds. That could be grip shapes that guide the hand, geometry that suggests direction, or mechanisms that make sense without having to read 41 pages of the manual. This matters because tools are often used under serious cognitive load (i.e., when you’re tired, rushed, distracted, or intensely focused). And you won’t make a slick dovetail when you’re using all your concentration to just keep your fingers attached.

Ergonomics

Comfort is one side of this. But it’s more about cumulative strain over time. For example, well-designed tools keep your wrist in a neutral position, reduce grip force through leverage and geometry, or even minimise awkward angles and repetitive motions (where possible). So factors like handle cross-section, diameter, texture, and material all matter – especially under sweat, vibration, or long sessions.

Mechanical honesty

Also like my aunt, great tools are ruthlessly honest too. They know what they can and can’t (or want and don’t want to) do, and they honour it. Almost like self-imposed constraints. And I think this has an important mental benefit, one many of us don’t realise: you know this tool's job, and you stick to it. No prying open paint tins or hammering the life out of it because it looks like it could take a wallop.

But on the flip side, when failure does occur, good tool design makes it obvious and controlled. For example, a visible bend, a sacrificial part, or a clear limit – not something that’s going to surprise you later.

Timelessness

The tools people keep for life are rarely disposable by design. If something has been well-designed, you naturally want to look after it, frame it, worship it, and defend it with your life.

And the tool stays useful. Yes, part of that comes from fixing timeless problems… but it also means the tool needs to age well. Not just a pile of dust and shavings.

Longevity is a huge part of our ethos at MetMo (we offer 200-year guarantees on everything we make) because we know the value they can bring as heirlooms. As your tools pick up scuffs and scratches, they begin to tell a story of everything they’ve made or broken – a story your grandchildren’s grandchildren can potentially experience. And to me, the best-designed tools last long enough for this to happen.

An exception would be tools that are designed to be disposable. But you’re not really expecting them to last, so… that brings me nicely into some other tool design contradictions.

Design contradictions

One reason tool design is so hard to get ‘right’ – and why ‘right’ is so fiercely contested – is that many of the rules designers follow are only conditionally true. Few principles apply universally, and most depend on context. Knowing which rules to follow, which to bend, and when to ignore them entirely is what separates good designers from the bad.

What’s more, it’s the context that actually determines what’s important for the tool and what’s not. Think, a tool designed for a pocket, a bench, or a job site, is solving different problems each time. It’s like the lens through which the tool/designer sees the world.

This is also why many assumptions that we instinctively label as “good” (e.g., lighter, simpler, stronger, or fewer features) can become liabilities in the wrong situation. Which is where some of the design contradictions begin…

More is better vs less is better

Generally, less is better is better. Fewer features. Painfully simple. Anything that doesn’t serve* should be removed because extra functions add weight, bulk and complexity without being used. This increases cognitive load when we use them and pulls us away from the core job the tool is supposed to do.

Ah, but…

A multi-tool without multiple tools is just… a… tool. Or if you’ve only got 16 toolboxes, then tools that double or triple up let you fill your boxes with more. Big win.

*To be fair, this can still be applied to multi-tools, but you get my gist.

“It must be lightweight”

Weight is often treated as an enemy in tool design. For anything you carry daily, unnecessary mass quickly becomes a reason not to carry the tool at all. But again, exceptions apply.

In some tasks, weight improves performance and function. Take axes, planes, chisels – these benefit from extra weight because it reduces required effort, improves stability and control, and dampens vibration too.

Weight is also a common heuristic for ‘quality’. So if you’ve just bought an expensive tool and you’re expecting it to be heavy – and it’s not – then you’re going to be disappointed and our brains actually (seriously!) tell us it’s worse than what it is. (Check the Expectancy Theory to see why)

Specialisation

In a workshop, the best tool for the job usually wins. A specialised tool is generally faster, safer and more comfortable. (It’s also a great excuse to keep buying more tools)

Outside the workshop, that logic flips. In EDC, travel or field-use, versatility matters more than ‘peak performance’. Carrying one tool that does enough jobs well is often better than carrying none of the perfect tools.

Rules? There are no rules

So the context of the tool is very important. The ‘problem’ being solved, the environment the tool lives in, and the way it's actually used all determine what's acceptable and what isn’t. That’s why so many design “rules” end up bent, broken, or selectively applied.

With that in mind, here are 5 tools I consider well-designed. (No affiliates or anything here, just my opinions)

5 well-designed hand tools

1 - Gyokucho ryoba saw

The ryoba saw is a saw that’s used in fine woodworking, joinery, and controlled cutting. And the big difference to ‘conventional’ hand saws is that it cuts on the pull stroke instead of the push. Because you’re pulling, the blade stays in tension, which means it can be paper-thin (cutting a much narrower line and requiring less effort from you)

One side of the blade has rip teeth, the other has crosscut, so you can use it in more jobs.

But there is a bit of a challenge – contradicting rule 2, I know. With a ryoba saw, the effort you need is sooo much less. Almost an unnatural amount less. And this can be weird at first. But this is what gives you the control that makes them so damn good.

2 - Olfa Snap-Off Utility Knife

“The best-designed tools last long enough for this to happen.” I know, I know, another contradiction. The context is different, alright!

A long-lasting knife that you can pass down through your family is great – and sharpening a knife is a lot of fun too. But sometimes that’s not what you need. The blade of the Olfa Snap-Off knife snaps off, so you can always use a sharp edge. It’s thin and has adjustable reach, making it great for all kinds of situations. (It’s also a cheap alternative, protecting your pocket knife for more special or creative occasions.)

In this context, intentionally designing for failure – frequent, controlled failure – actually produces better outcomes than chasing an heirloom. Another great example of an brutally honest and opinionated ‘Aunt’ tool.

3 - Knipex Cobra XS

This is one for my EDC gang. The Knipex Cobra XS is a great multi-tool plier replacement. It’s lighter. Sharper. And slop-free. Thanks to its self-locking button, once you set it, it clamps and stays put.

This is an example of one of those ‘painfully simple’ tools. It’s timeless. Honest. And still opinionated about what it can and can’t do – because the XS is clearly in no way a replacement for bigger pliers.

Of course, the best feature is its size. It’s tiny (~4 inches) but tough. And more than earns its place inside your pocket every day.

4 - Victorinox Pioneer X

Oh, look, another rule breaker. Here, the concept of more being less. Because we’ve got 8 tools in a humble 93mm aluminium body.

The Victorinox Pioneer X is used in everyday carry. AKA light tasks and unpredictable needs. Which my life seems to be full of these days. With this Swiss Army Knife (SAK), the tools are practical… and beefy. For example, the awl* is a great daily driver for box opening, scraping gunk, poking holes in tins and slashing packaging. The knife is also larger, the screwdriver more sturdy, and the whole tool generally feels more reliable than a lot of other Swiss Army Knives.

So more features are valuable – if they’re the right ones. And my final tool takes that to another level…

*Did you know the awl was originally added to a SAK for the cleaning, assembly and disassembly of a rifle? We’ve just found more uses for its stubby pokiness since. Timelessness, eh.

5 - Leatherman ARC

Complexity is sometimes necessary (and worth it). Now you can have damn-near everything in your pocket at once. The Leatherman Arc is used for outside environments, but depending on what you do, you might need it for work, travel, or even rescuing baby pandas from fire-breathing dragons – because there isn’t much the ARC can’t do.

I really like that you can use one hand for everything. And that’s not an easy thing to think of for the first time. In this design context, simplicity of use matters more than the simplicity of construction. And that’s a huge thumbs up.

Same rules. More metal.

Each one of these tools breaks at least one “rule” and gets away with it because its context demands it. The Ryoba ignores mass and rigidity in favour of precision. The Olfa sacrifices durability for consistent performance. The Knipex balances pocket-friendliness with strength. The Victorinox proves that more features can be better. And the Leatherman cranks it up to 11, showing that complexity is justified when it removes usual friction (of use).

So, good design is a matter of applying rules and principles intelligently. And where necessary, bending and breaking them too.

But there’s one rule I’ve intentionally not mentioned – that all of the above tools adhere to: satisfaction. What good is any tool that isn’t fun to use? Enjoyment is a somewhat immeasurable metric, but it matters more than most.

And we, at MetMo, do our best to engineer-in satisfaction alongside applying the above principles intelligently to our own creations.

MetMo Driver

This is our compact, high torque driver that unites the old hand brace and the new(er) ratchet screwdriver. Every click is meticulously crafted to give you maximum satisfaction.

Learn more about the Driver, and see everything it can do here.

MetMo Grip

Say hello to the world’s most satisfying grip. Its 316 stainless steel jaws will clamp and hold anything (that fits inside) with ease. It also has a bottle opener, a box opener, and a standard ¼ inch bit holder too. Then, if you want to use the end as a lil’ hammer, to fix those lil’ annoying knocking problems, we designed for that too.

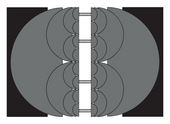

MetMo Fractal Vise

And then our beloved Fractal Vise. Made of 6 independent arcs (that move freely), our vise can clamp anything of any shape. We made this specifically for the desktop makers and breakers. Check it out here.

It just needs metal

There’s no single formula for good tool design. What works in a workshop doesn’t always work in a pocket. What’s perfect for daily carry can be frustrating on a bench. So the best-designed tools aren't those that follow design rules rigidly – they’re the ones that know when to break them, and are good fun to use too.

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading this. If you have tools you think are well designed that nobody talks about, tell us in CubeClub or our Subreddit. We’d love to hear from you.

See you in the next one.

Share:

Pocket science explained: The best 5 types of EDC tools in 2026